Albany Bulb

Susan Moffat

The Albany Bulb is a widely loved, sometimes despised and surprisingly well-documented dump. Google it and thousands of photos will appear: fanciful sculptures, spectacular waterfront views and lots of dogs. Architecture and landscape architecture studios from several universities have used it as a laboratory, several documentaries have been produced, and many articles on the site as a political battleground have been written both by journalists and by scholars (see, for example, GROUND UP Issue 01). The physical Bulb has been represented through maps and diagrams produced by students in studio courses. These show a near-island, somewhat larger than Alcatraz, made of construction debris and attached to the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay by a long dirt neck. In cross-section, it is lumpy: dumping at the Bulb continued from the early 1960s to 1983, but the landfill was never fully capped.

However, the social Bulb has never been properly charted spatially. Human activity here is many-layered. For years, artists have used the landfill’s concrete slabs and rubble as canvases and its rusted rebar and driftwood as fodder for sculpture. Dog walkers, paintballers, mountain bikers and birdwatchers have created a network of trails. Kiteboarders have shared the small beach with children and dogs, and a theater troupe called We Players staged an outdoor performance of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The Bulb has also been a place of human habitation for several decades. Self-described hoboes, poor people and urban experimenters have used the landfill as space for living. They shaped the space to meet their needs, creating a community of homesteads, infrastructure, and landmarks of creative and varying designs.

By 2013, the number of Bulb squatters had swelled to an estimated 70 people and a large number of dogs. Following lobbying by the Sierra Club and Citizens for Eastshore Parks, the community was evicted in early 2014 to make way for the McLaughlin Eastshore State Park, which stretches 8.5 miles from Oakland to Richmond.

Some months before the planned eviction, I started a project to capture and anchor in place the human stories associated with this place in a project called the Atlas of the Albany Bulb. The Atlas is a collaborative, participatory, multi-disciplinary web-based project that collects oral histories and maps the site with the help of former squatters, local residents and park visitors. The project is ongoing and welcomes submissions representing all points of view.

Working with UC Berkeley students, I distributed disposable cameras to Bulb residents before their eviction and helped them record narration for the photos they took. We asked people to help us map their homes before demolition, as well as the many public spaces they had built, including places known as the Amphitheater, the Library, the Yellow Brick Road and Mad Marc’s Castle. We measured and mapped the trees that formed the frameworks of their homes and conducted video interviews. We created interactive online maps of the ever-changing art.

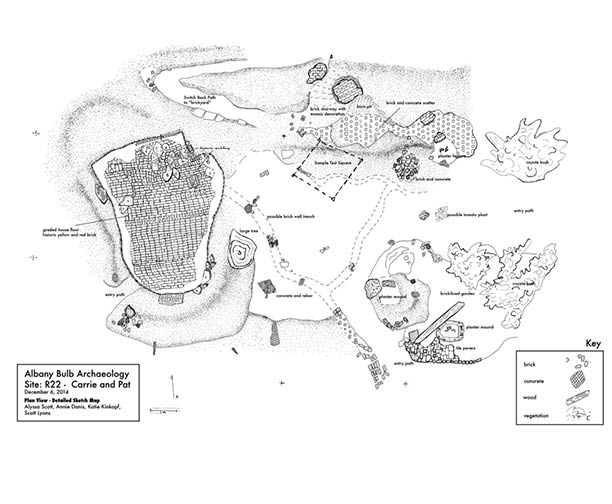

After the eviction, archeology students, in consultation with former residents, mapped the elaborately laid brick foundations that were left behind after the huts and tents were swept away. Residents and their friends reflected on tape about the human and natural history of the space, creating stories that students from the Information School are developing into a site-based oral history audio tour app.

We presented these slideshows, maps and videos as part of an exhibit called Refuge in Refuse at San Francisco’s SOMArts Cultural Center in February and March 2015, which was curated by Robin Lasser, Danielle Siembieda, and Barbara Boissevain. In addition to excerpts from the Atlas, the exhibit also included art that was formerly located at the Bulb, as well as art photography and photo montages portraying the Bulb. Randi Johnsen’s UC Berkeley landscape architecture students also contributed images of proposals for the site that they had developed in their studio class.

Through these multiple processes of research and representation, we asked: How can one adequately represent a landscape as multi-layered as this—a palimpsest of urban debris, invasive species and overlapping strata of memory and legal jurisdiction? Maps of topography, vegetation, trails, art and encampments help, but are inadequate. Maps of the imagination and of individual experience are also required.

Verbal narratives add a chronological aspect to the spatial dimension, but representing time and story on a map is challenging. Technology such as mobile platforms and augmented reality can help locate and deliver stories both onsite and online. However, the more effectively interactive platforms mirror the fragmentary nature of experience, the less they convey the kind of single story line that often helps us make sense of the world.

Analytical tools from the social sciences are important, but humanistic approaches to discerning the experience of place and of the human relationship to nature are also necessary. Artistic expression—the creation of art both at and about the Bulb—is important not just as a representation of place, but as an investigative and experimental method.

The arts and humanities have a crucial and underutilized potential for informing better design of cities and public spaces, not only by capturing the human dimensions of space, but by asking questions of meaning and ethics. Exploring the potential for this interplay of the design and humanist disciplines is the central work of the Global Urban Humanities Initiative, a three-year experiment at UC Berkeley that brings together scholars and students from several dozen fields. The Atlas is one small part of this initiative. One important question is how our plans to intervene—or not—affect how we see and represent a place.

Students of landscape architecture, beginning with an intent to design, mapped the spaces of the Bulb with a different eye from the archeology students, who were focused on documenting but not altering. Both groups of students, however, gave careful thought to the ethics of their work, and many took time to talk with residents or former residents whose spaces they were representing.

The project brought together scholars and practitioners from different fields, and we learned that the rules of the road were different for different disciplines. Preserving the anonymity of people portrayed in research was required in some social sciences, while giving people the opportunity to express their stories as individuals with names and identities was essential to oral historians. The very notion of considering interviewees as “human subjects” in need of protection by research protocols rather than as agents of their own narratives and lives was troubling to some people.

We faced profound ethical questions. Osha Neumann, a long-time advocate for the people who lived at the Bulb, objected to what he saw as artists “aestheticizing” the experiences of Bulb residents as art for outside consumption. He also critiqued academic researchers for studying a problem without taking action to change outcomes.

In the end, we were forced to question the role of the university and of the white cube of the art gallery as frames for lived experience and landscapes, even as we relied on these institutions to make our work possible. We also faced very real problems in the connection between theory and practice, and between documentary and projective, action-oriented work. What is the difference in the moral position of someone designing changes to a place of human habitation, and someone recording the destruction of that community? Intervening and observing are equally fraught.

Susan Moffat is the editor of the Atlas of the Albany Bulb, part of the UC Berkeley Global Urban Humanities Initiative, of which she is Project Director. Moffat has worked in affordable housing development, environmental planning, and journalism. The Atlas is being produced with the support of the Cal Humanities Community Stories grant program, and the Global Urban Humanities Initiative is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.