THE CORE OF IT: interview with Dutch landscape architect Michael Van Gessel

GROUND UP: How do you perceive the genius of the place?

Michael van Gessel: People perceive the genius of place with different awarenesses, so it’s not something absolute. The genius of the place is something that you discover by being sensitive, by being perceptive, by listening, by just being, having an awareness of what is going on around you. The temperature, the climate, the atmosphere, that is all about the genius of the place.

The other thing that fascinates me is the history [of the place]. I always study what was there previously. It allows me to understand why the place is as it is.

GU: How do you think the past and present could be incorporated into the future of a site?

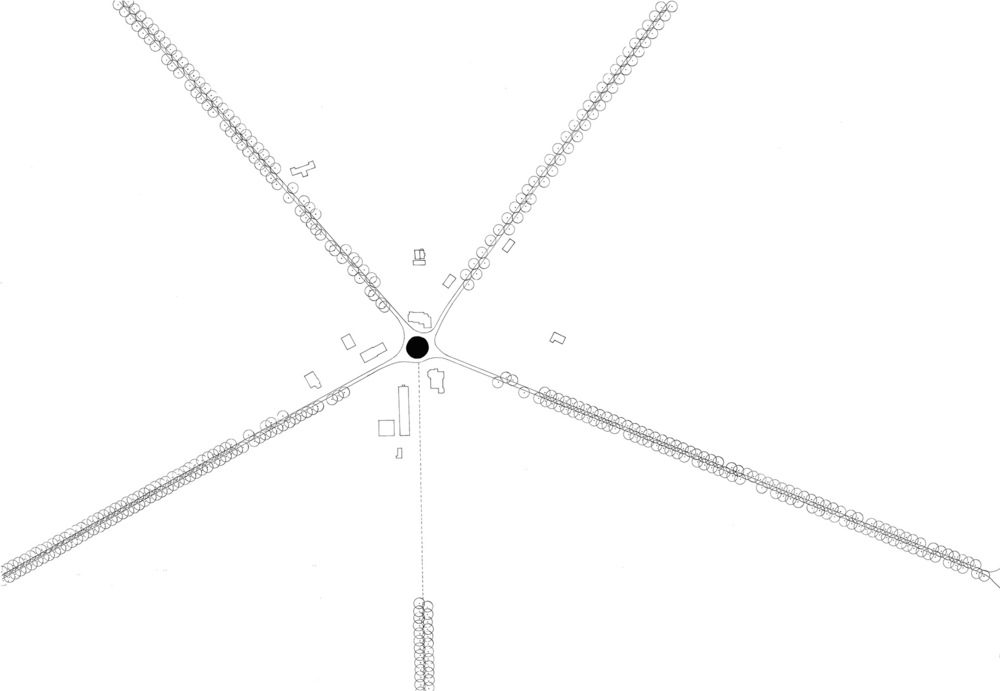

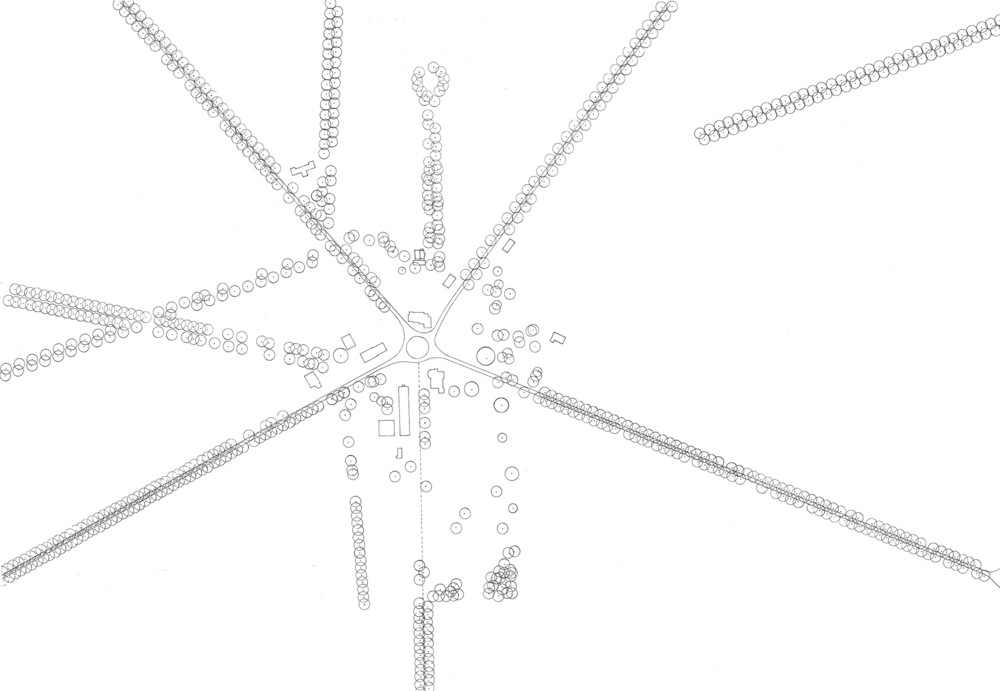

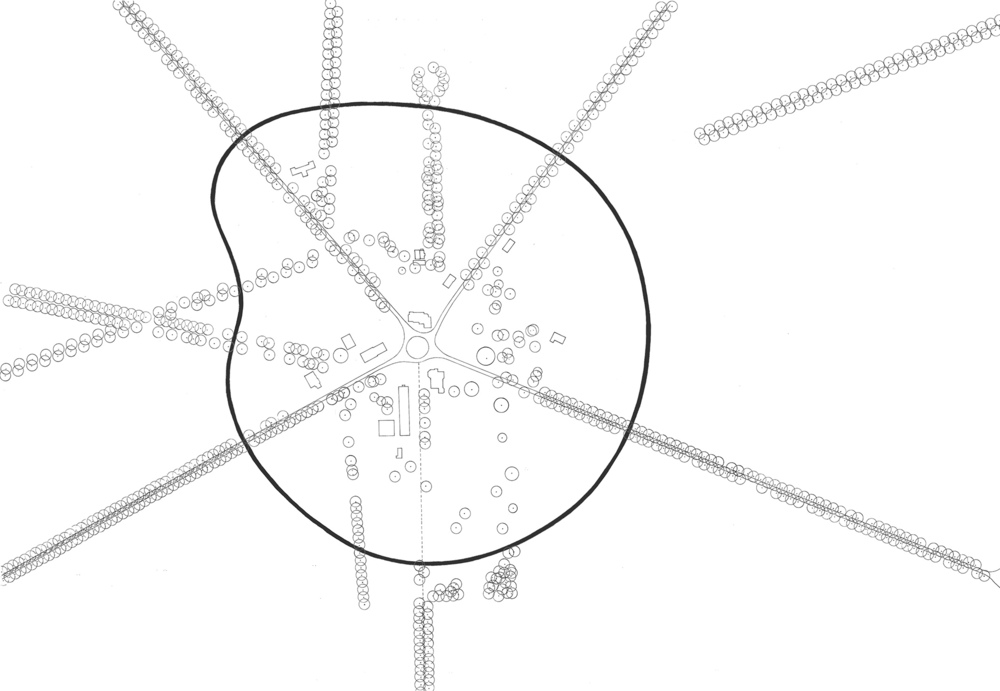

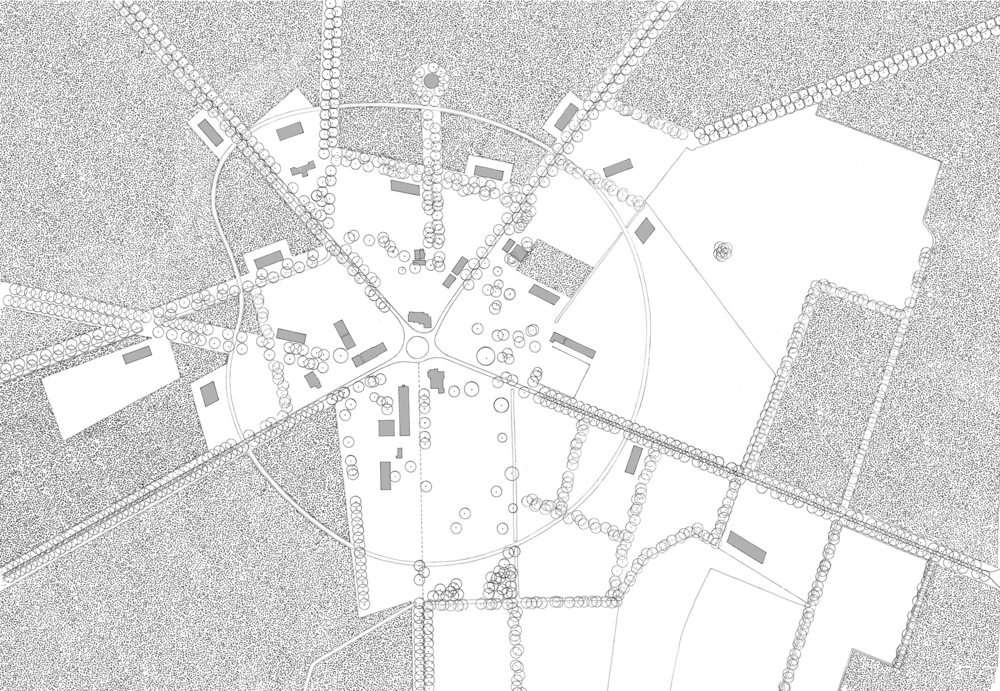

MVG: If a site has a complicated history, it takes time to understand why it is as it is. In any case in design, you first have to understand before you interfere. I like to interfere as little as possible with a maximum of result. Maybe there’s no human history, but there is a natural history. If you understand this, how geologically it became as it is, then you can work with nature—you don’t try to force the site to do what you want. It is more interesting, more ecologically sound, and often more beautiful than when you interfere with design. I think it is better to interfere by process, by doing something like acupuncture, where you act somewhere and the energy flows to other parts, creating something surprising. When you hardly interfere, you are [still] able to generate a huge amount of result. That fascinates me.

“People have thousands of ideas, that’s not difficult. Having the right idea in the right place is what matters. Site and your intervention should go together and grow into something much more powerful. ”

GU: What is the position of site in a complete design process?

MVG: The site is the main thing. We, as landscape architects, are always site specific and ground specific. That is by definition.

When I was younger, I would feel this drive to create, to make. I’ve learned that it is better to first see what things come out of the site. It is very egocentric to want something. When you don’t come from a place of wanting, life, or the site, will give you things to discover, and they are often very unexpected.

It could also be that society asks you for something, be it a commissioner, a social constraint, some issue with the site—these are separate influences, and you try to bring them together. But first of all it is a question of respect, of holding back, seeing what the site gives you. That is what interests me.

I see that designers want to interfere, they want to do a project. I see it also with the students. I ask them, “Why this? Where does this come from?” It will be a pattern they made up, an image they found on the internet that inspired them. But it’s just an idea. If you go site specific, it’s not an idea, it’s the site! It’s the character and the genius of the place. People have thousands of ideas, that’s not difficult. Having the right idea in the right place is what matters. Site and your intervention should go together and grow into something much more powerful. I’ve learned that my best designs are when I listen as closely as possible, and completely without prejudice, without having something thought out in advance, being as open and receptive as possible. In design, it is between making a forceful intervention, and being sensitive. You are powerful, decisive, driven, but also very quiet, very subtle, very focused.

GU: You have said before that landscape architecture is an applied art, and our work is in the service of the site. Where do you find the balance between the client’s demands, the designer’s artistic intuition, and the site itself?

MVG: I see it more as the site and the client. You are just the catalyzer. You try not to be the third person, but to listen to the client. The client will often come with a solution in mind, and I will get them to see that the design can be done in different ways than they think. That is your job [as landscape architect]—analyze, go to core of it, understand what the site can accommodate easily. Because the site is so specific, it can transform the client’s demands, producing a very different solution than what they had imagined. As a result of looking at the site, I often did something completely different than the client expected, or than even I had expected. That is openness. That is applied art.

GU: You talk about the historical and geographical aspects of the site. What is the importance of culture in your reading of the site?

MVG: It is just as important. If you look at any site, you will see that human intervention and natural conditions grow together, they merge into something. When you change the human intervention because of an assignment, you change that intricate balance between what we want and the natural possibilities and restraints of the site.

When you are dead, people will do whatever they want with your designs, with your parks and your plazas. You must always think that you are just an intervention in one time and space, and that time will go on. If you defend [your design], it won’t work. You must always look at what is essential about your design, and be adaptive. New demands will arise, and you will need to change things, but I like that. That is life giving you a new design opportunity. The designer’s role is to think broadly, to be able to change. It doesn’t matter what the design is, as long as it is well-designed.

GU: You have worked at many scales and in many settings. What are the challenges of working in these different contexts? How do you manage to read the place in different conditions?

MVG: It is always about attitude, and that can be applied to all scales. Your own identity is ingrained in your design, so you [inherently] do things differently than someone else would. That doesn’t matter, as long as you don’t have [your individuality] as an authoritative goal. I always think, “I’ve never done this before,” but when I look back at all my projects, I can see my handwriting in them. I can see that they are mine from what I took out of the site. Of course, you can take many things out of a site. That is what makes studio [projects] so nice. Everyone has the same site, but each student does something different.

People worry as designers, “I must be unique!” You don’t have to worry—you are unique! You don’t have to invent something that others have not yet done. If you go to your heart, [your design] will be unique.

Of course I understand [this concern]. I wanted to study architecture, but I thought, “No I can’t. I have no creativity!” But you don’t have to be creative. The site and the question and time give you a different solution every time, and the red thread [connecting these solutions] is your personality. And that will come by itself. Don’t work on it, it will come.

What I do work on is attitude. I read, I think about society. I also try to give society something that is new or that brings us a step forward. It is not only about beauty, but also about inclusiveness, flexibility, [design that] many people can use. You always have to develop. If you don’t develop, you become conservative, [thinking that] the past was better than now. Nonsense! It’s much better now.

GU: You’ve had nearly four decades of professional experience. What was your transformation through this process? Are there particular projects that exemplify an evolution in your professional life or your approach to design?

MVG: There aren’t epiphanies—it happens gradually. Things happen in life, and you grow. I studied tropical plant diseases at first, but then I went with my heart—I knew I would always regret it if I didn’t give [landscape architecture] a chance. I was first working in a group, and then on my own. Over time, I came to understand myself as an artist, but not in the strict traditional sense. There are people who are artists, who are very good at drawing, but I’m a good applied artist, because I listen well and I can explain well. To be good at this job, you must be a good communicator. It’s often about selling yourself and [expressing] your intentions, your generosity, your sensitivity, and not about your projects. Clients don’t always understand drawings, but they will trust you to do your work if you can communicate with them.

I was brought up in modernism, when everything was rationally defined. Later, we got post-modernism in the 1980s. Everything was a design on top of a design. [Think of] La Villette. We were thinking of layered elements, and we realized that we can also layer nature. In my design, I borrow a lot of patterns from nature, because no one can design as beautifully as things happen in nature. I never liked post-modernism. Everything is over-designed, so many materials, it’s so tiring! I love good ingredients and simple elements—grass, trees, a concrete wall, that’s it.

We won a design competition in Warsaw calling for a “Garden of the 21st Century.” In my opinion, the garden of the 21st Century is nature. They wanted the garden to go with a large museum, but the museum was so big that the garden was insignificant, so we put the museum underground, and the garden undulating over the top of it. The garden is filled with plants, which are to be left to grow and interfere [with each other], developing on their own. It’s playful and relaxed, and doesn’t need to be taken care of like La Villette, where everything must stay in a certain shape. The design works with nature and change.

I defended modernist neighborhoods because they were made out of great idealism, [the notion] that people could make a better world after the war, which is lovely. You can see now why it didn’t succeed, so you have to take those negative aspects away. Over the last forty years, we have grown into very individual people, which is not bad, but different. We want to be free, and this is good, but we are not a society taking care of each other any more. So, we have to adjust environments that were made with the thought that people look after each other, because these environments don’t work any more. We have to transform them without destroying them.

Michael van Gessel received his education in landscape architecture at the University of Wageningen (1978). Since 1997, he has practiced as an advisor in the broader field of landscape architecture and urbanism.