xe/xem/xer are gender-neutral pronouns. Read more about gender-neutral pronouns on the website of the Gender Equity Resource Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

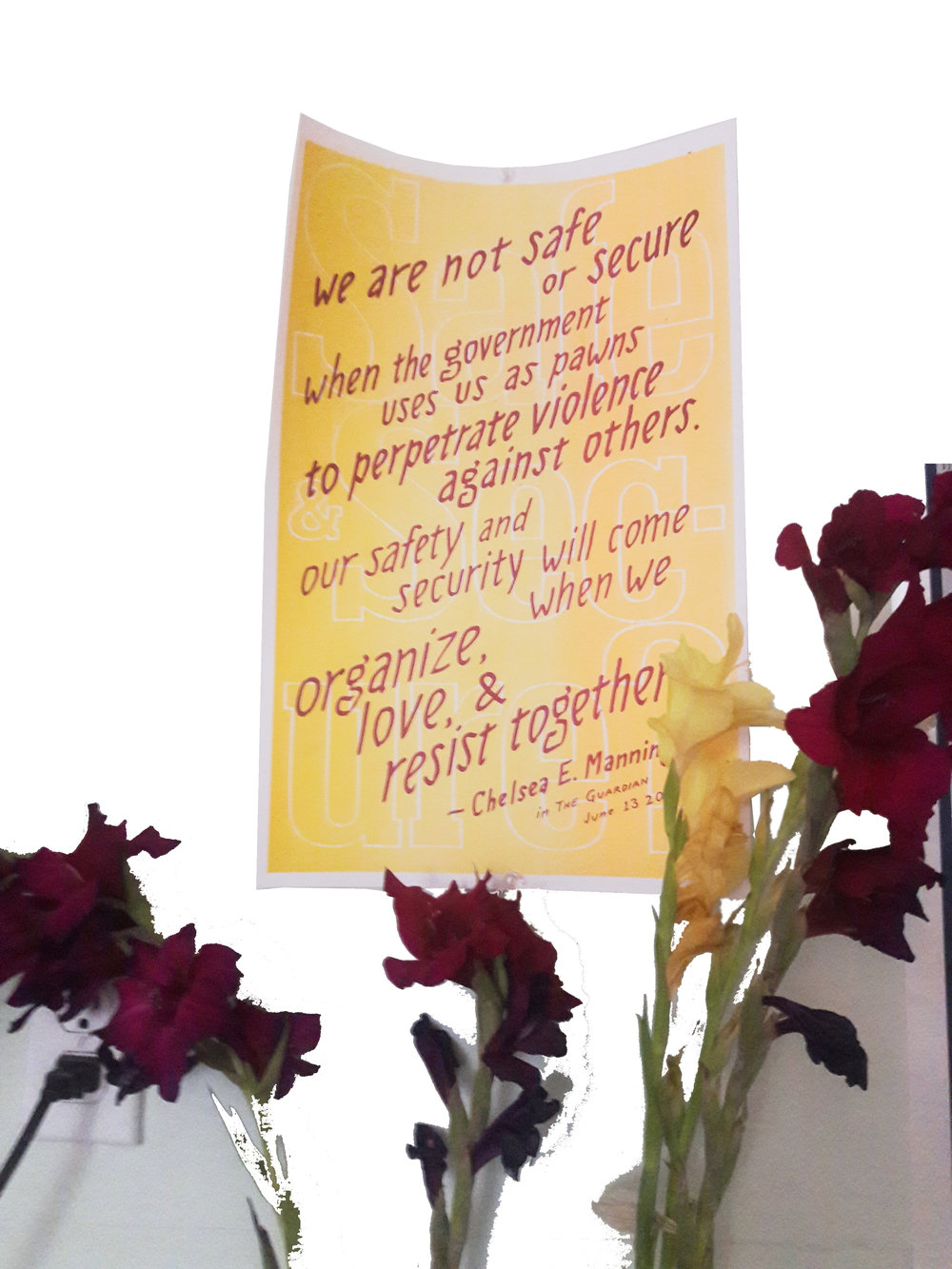

Vigil in Providence after the Pulse nightclub shooting. Photo by Ash Trull.

Illustration by M.J. Robinson, mj-robinson.com

“Reborn,” a film by Luisa Piña inspired by her coming out. Photo by Daniel Oliver.

Photo by Ash Trull

Art by Lindsey Medeiros

Photo by Ash Trull

My Queerness, My Community:

Stories from the Landscape of Personal Identity &

its Consequences for Future-Building

By: Judee Burr

“A lot of current queer language is new and is strange, right? Because it’s literally creating language where there was no language before,” says Justice Gaines (xe/xem/xyr), a 23 year-old poet and community organizer. Xe works for Rhode Island Jobs with Justice on an initiative to establish community protections against police violence in Providence. Xe laughs as xe describes liking “to force people to think a little more” with xyr pronouns.

“I identify as a black trans woman, and I also identify as genderfluid,” Justice says. “The first thing I came out as when I came out as queer was demisexual and asexual … For me, it was a process of learning these labels and being like: one—that’s wild. Then two—wait, that sounds kind of familiar. Huh … That language is actually speaking to an experience that I had literally no way of naming before.”

Queerness is a landscape unto itself

Queerness is a landscape unto itself—an inclusive identity beyond the gender or sexual binary, a political statement, and a word laden with pejorative meaning for many members of the gay community. Queer individuals are navigating their personal identities amidst a LGBTQIA+ movement that is growing—whether judging from numerous surveys of the more-likely-to-be-non-conforming Generation Z, the increasing number of gender and sexuality options listed on sites like OkCupid and Facebook, or the record number of queer characters that are appearing on the television programs shaping our inner narratives, shows like One Mississippi, Transparent, and Orange is the New Black. More people are diving into the open waters of gender and sexual identity and resurfacing under the queer umbrella, with consequences for the futures we plan and the communities we foster within them.

This piece weaves together stories from queer artists, educators, farmers, community organizers, coders, and others to examine their personal landscapes of queer identity. These inner mappings are not uniform. Rather, they embody the grappling, disagreement, and rebellion inherent to queerness, a practiced comfort with standing up and standing out. In bucking social pressure to conform, queer individuals have been forced to act as architects of the self, re-casting their own molds, spitting out assumptions, and delivering the consequences of this personal work to the communities they live in.

From the Stonewall riots led by trans women of color and gender-non-conforming activists, to intersectional queer feminist activism of the 1980s and 90s, to the Black Lives Matter movement, queerness has had the reputation and consequence of social transformation. The deep and personal journey embedded in queer experience, of norm-toppling and identity-finding, impacts our communities beyond gay-coded spaces. An important look ahead emerges from the perspectives to follow—futures through a queer lens confront business-as-usual practices with a honed skepticism of ‘the ways things are,’ with the boldness to envision more powerfully the way things could be.

PERSPECTIVES FROM THE LANDSCAPE OF QUEERNESS: FINDING THE WORDS

“I felt like I had to make a decision as to what I identified as, I felt really strongly that I had to find the word. And I felt really strongly that I couldn’t,” says

MJ Robinson (they/them/theirs).

MJ is a 25 year-old artist, community organizer, and a museum educator with the Rhode Island School of Design. They now use the word queer to describe their sexuality and gender queer or trans to describe their gender. Growing up north of Philadelphia at a time when they knew only a couple other gay people in their high school, they remember feeling a lot of anxiety when coming out. “The most intense wave of panic consumed my body,” they say, describing one night a crush cuddled close to them.“ That was sort of my trigger that I need to figure shit out.”

Words map the expanding landscape of queerness. Discovering explanations and labels that subvert dominant narratives about gender and sexual

identity and using them to name one’s reality is a formative experience for many queer people. These words can capture an experience outside the box of heteronormative romance and the confines of the ‘man-or-woman’ gender binary that structures most lives from childhood. Some interviewees recognize queerness in their earliest memories. Others recount specific experiences and people that helped crystallize their personal identities later in life. Many describe adopting and then changing the words they use to explain their gender and sexual identities. Few personal landscapes remain static.

Steph France (she/her/hers) first heard the word in second grade at her all-girls Catholic school, where she remembers lesbians often getting teased. “Mom, I think I’m a lesbi-OWN … I like girls,” Steph recalls saying when she cornered her mom doing her hair in the bathroom. “And she’s like: ‘Oh, I know that … Of course I know.’”

Steph France and Rowena Jones (she/her/hers) are both 29 years old and live together in southern Rhode Island. They have been dating for five years. Steph works independently as an actor and together with Rowena to manage a business selling books and other retail through Amazon.

Steph remembers feeling ‘like a dude’ when she was growing up in southern Rhode Island. She became comfortable identifying as a woman in her late teens. “Not all women have to be super feminine, not all women have to fit into the stereotypes,” Steph says. “I’m not going to call myself a guy because I’m masculine. I want to put it out there that women can be whatever they want.”

Rowena also identifies as a lesbian and remembers some of the judgment she faced when exploring her own identity. “She didn’t think at all that I could possibly not be into guys,” Rowena says of her mom, remembering getting ‘the talk’ from her about sex and relationships. “That affected me. I tried to be with guys until I was in my twenties,” Rowena says. “It really messes you up and confuses you when people tell you what you are.”

There is a loud, societal story about relationships and gender identity that a person must confront with distrust in order to name their queerness—a story that offers two gender options and tells us how men and women are supposed to dress and behave, what genitals they’re supposed to have, and who they’re supposed to love. Being queer is an act of questioning one or more of these stories. Queer people must fight to create spaces in a society that continues to privilege straight and cis-identities and experiences.

Toby (he/him/his or they/them/theirs) works in the field of sexual health and sexual violence prevention on a mid-sized university campus. (Toby is not his real name). Toby identifies as transgender and queer. “I think a lot of queer and trans folks find themselves drawn to information, because so many of us are not afforded information about our identities,” Toby says. “I remember the first time I heard the word transgender and transsexual, and I was definitely overwhelmed with my own transphobia. I really tried to play the game,” Toby says. Then I finally realized the game is rigged ... The truth is that vanilla, straight, cis-gendered-ness is such a tiny slice. And any time that any one of us, it could be argued, steps a foot outside one of those boxes, we’re experiencing queerness.”

I finally realized the game is rigged

…The truth is that vanilla, straight, cis-gendered-ness is such a tiny slice. And any time that any one of us, it could be argued, steps a foot outside one of those boxes, we’re experiencing queerness.

There are generational differences in the ways queer people choose to identify. In a study comparing Generation Z (age 13-20) to Millennials (age 21-34), significantly more of the younger generation reported knowing someone who uses gender-neutral pronouns (56% of Gen Z versus 43% of Millennials). College campuses are increasingly providing resources for transgender and gender non-binary students, and introductions that include each person’s preferred pronouns are becoming a new norm on many campuses and in other community spaces. Yet, historically, and presently in many places around the country and around the world, queer-identifying persons have been forced to remain ‘closeted’ and hide their gender and sexual identities for fear of violence, discrimination, or non-acceptance from their families and friends.

“At this moment, I consider myself to be a woman and my pronouns are her, she, but I feel like if I was born in the 2000s and I was an adolescent at this time, I would probably be more comfortable calling myself gender-neutral or something like that,” says Luisa Piña (she/her/hers), a 32 year-old Venezuelan filmmaker who lives with her wife in southern Massachusetts. “I’m very comfortable with my body, I like my boobs and my vagina. I’m just upset that just because I like my body that puts me into something.”

“I never hid it,” Luisa says of her lesbian identity, thinking back on coming out to her Catholic and conservative family in Venezuela. “I was brave enough to come out, still at 15, and the first person I told was my mom,” Luisa says. “I was strong in my belief that I needed to be out there, even if they treated me like shit. Because, especially in Venezuela, you don’t see it out there. It’s not like we don’t exist, we are there. We’re just hidden. And it’s not fair.”

In her first two relationships, Luisa dated women who were not open about their queer identities. She describes this as a challenge. “I was out and I felt comfortable and I wanted to hold their hand but they didn’t feel comfortable,” she says. Luisa says that dating someone who was also out was an important milestone; bringing a partner home who was open about their relationship helped her mom accept her as a lesbian. “This partner was not afraid to hold my hand at my house and be there like ‘I’m Luisa’s partner.’”

Lindsey Medeiros (she/her/hers), a 33 year-old farmer, grew up in a religious, working class household in Massachusetts, with a Catholic father from Portugal and a Jewish mother. She became comfortable living as queer when she moved to New York for college. “I’ve always considered myself to be a tomboy, even when I was four,” she laughs. “I consider myself to be genderqueer, but I feel not right using the they/them because I feel it takes away from people who are transitioning and that’s not the space I want to occupy.” Now she uses the words lesbian, dyke, queer, and gender queer when describing her gender and sexual identity.

Even in queer spaces, people grapple with the validity of their personal experiences and the feeling that there is a standard of queerness to live up to. Many queer people feel confined by norms perpetuated by both the straight and queer communities.

Ash Trull (they/them/theirs), is a 30 year-old community organizer, facilitator, coder, and farmer in Providence, Rhode Island, who identifies as non-binary, queer, and genderqueer, occasionally using the term AFAB, or ‘assigned-female-at-birth,’ to describe their identity. “I’ve chosen a lot of different words for my gender over the years, and a lot of times it’s just like meeting someone whose gender I resonate with and then hearing what they say and being like ‘oh yeah! Non-binary! That’s me,’” Ash says.

Ash explains that, as a non-binary person, they have had to use the term AFAB—assigned-female-at-birth—to gain access to spaces more explicitly marketed to women. “A thing that happens in identifying as non-binary or genderqueer is feeling like I lose that solidarity with femmes or with women,” Ash says. “AFAB is something that’s really helpful for me in talking about my socialization, my upbringing, what gender I was assigned, and then pushed into for a huge chunk of my formative years.” As a queer coder, Ash has gravitated to communities like ‘She Hacks’ and ‘Lesbians Who Tech,’ but notices the ways in which non-binary identities are invisible in the title font of these gatherings.

“I feel like we’re missing something if we can’t get all people together who suffer from gender oppression,” Ash says. “There’s complexity to the way that you experience privilege and oppression, but we have to be able to hold that so we can support each other.”

Privileges and Threats

Coming out as queer and openly adopting queer-identifying labels is challenging and often dangerous—many individuals in the United States and around the world face enormous pressure to live up to straight and cis-gender cultural norms. In many places, this pressure takes the form of open, violent discrimination. In the United States, as of 2017, people can still be fired by their employers for being gay or transgender in 28 states; the 45th president has attempted to ban transgender individuals from serving in the military; and transgender individuals—especially trans women of color—are murdered at a disproportionately high rate. The second deadliest shooting in modern U.S. history happened at a gay bar, the Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

Around the world, there are more than 70 countries with laws that criminalize being queer. In Russia, anti-gay propaganda laws purporting to protect the morality of children have resulted in hate crimes against gay individuals and allow officials to imprison people for being part of the queer community. In Chechnya in 2017, the round up and torture of gay men—their crime: being gay—sparked an international outcry.

Lana (she/her/hers)—not her real name—grew up in Siberia and won asylum in the United States to escape Russia’s persecution of the gay community.

“I came out at a relatively young age … I wasn’t really thinking about the consequences of being open. It is dangerous because you actually have to be on high alert all the time, because you don’t really know what’s going to happen to you. You can be attacked by your classmates or you can be attacked by your neighbors or people on the street if they know that you’re gay,” Lana says. “And moreover, nothing is going to happen to them.”

In the United States, the transgender community has also been more visible in recent years and there has been a reciprocal backlash. “Queerness is much more widely accepted, trans-ness is so misunderstood,” Justice Gaines says. “We’re at a flashpoint for trans identity where you’re either going to accept it and try to learn, or you’re going to push back hard.”

Justice also emphasizes that racial identity and class privileges significantly impact a person’s experience of being queer. The way trans people are portrayed in the media has a sizeable impact on public perception, and one of the most visible transgender women, Kardashian-connected Caitlyn Jenner, embodies a wealthy and white experience of trans-ness. Transgender people in the United States, especially transgender individuals of color, are at a high risk for extreme poverty. Poverty endangers lives and impacts an individual’s ability to be openly queer—financial resources often dictate whether a trans person can afford identity-affirming healthcare. When queer identity is only celebrated in the context of whiteness, as happens when white people uphold the privileges and power afforded by white identity ahead of grappling with queer oppression, queer people of color are harmed and abandoned by the queer movement.

“There’s no way to escape this idea that queerness and whiteness are tied together as long as we have a capitalist system. Because capitalism only benefits when something can be made white. And as long as queerness can be made white and not something more expansive than that, there is no real liberatory aspect to it,” Justice says. “Now that [queerness is] part of the mainstream culture, it also then has to be adapted to whiteness, and that’s why you have ‘Gays for Trump’ and you have all of these movements that can be anything that they want and be queer. With queer people of color, you can’t be a queer person of color and be anything you want.”

“The existence of queer people of color is at the crux of so many different levels of oppression, that we recognize that you cannot separate those levels of oppression if you want to solve a problem,” xe says.

Lessons from these landscapes of queerness, from those rebelling against the oppressive structures of a tired status quo, can be drawn into envisioning a fairer future: one that celebrates free expression, encourages the creative questioning of what has come before, and drives the construction of communities that uphold the rights and life-giving ideas of their constituents.

Consequences for Future-Building

Queer people are actively shaping communities, taking on diverse forms of engagement in political, artistic, and other social and work spaces to create the futures they seek. Queer individuals have long pushed the boundaries of dominant structures of society and self. But, in the age of the Anthropocene, an era of human-accelerated change for our physical landscape, there is a new urgency to re-envision the practices that have trapped us in a cycle of resource exploitation and environmental degradation. How does the multi-faceted landscape of queer identity translate to new visions for our local and global communities?

“You have to be able to imagine that it’s possible that it won’t always be this way,” Ash Trull says. “It takes a lot of creation and imagination and vision. And I think that is really deeply connected to gender liberation for me and sexuality and all forms of identity, that people can imagine themselves in a liberated form.”

Steph France describes her work to write screenplays that bring strong, genuine female characters to the screen. She imagines action films in which gayness is present but incidental. “A lot of LGBT movies are about being gay—I want to see a movie where there’s a gay couple and it’s fine,” she says. She is working on scripts with roles for women that break out of Hollywood tropes. “I’ve gotten told twice during auditions, ‘um, can you just be less—powerful?’” Steph says. “In reality, all women are not wimpy and vulnerable and super sensitive.”

Rowena Jones adds, “If you just take the main guy character and replace Steph with him, that’s her.”

Luisa Piña waves away the idea that being a lesbian has dictated her career choices, but some of her art connects to her identity. “I’ve always known that I like girls, even before I came out when I was 15, it’s so normal to me and so a part of who I am, it’s like me having brown hair. Does me having brown hair influence where I go to school? Not really,” she says. “Me being a lesbian does influence my art, but it doesn’t dictate what I do.” In the last year of her masters program, Luisa made an experimental film called Reborn about her coming-out experience. One of her current projects weaves in themes of being gay and working in the healthcare industry.

“It hits home for me in so many big ways,” Toby says of the connection between being queer and trans and doing sexual violence prevention work. “A lot of the people who are doing this specifically anti-violence work are usually white, cis-gender, straight women. So I feel super underrepresented. I am very well represented in the client base, in the people who have experienced harm, but I am not well-represented in the service providers,” Toby says. “I wanted to be able to have a say in my own destiny … I wanted to be a decision-maker about my own life.”

The community organizing work that Justice Gaines does directly addresses harm experienced by the transgender community. In 2017, RI Jobs with Justice supported a community-wide campaign to pass the Police-Community Relations Act in Providence, an act that includes protections for transgender individuals during police stops among other rights for community members. Now, the campaign is working to ensure the act is implemented to full effect. Justice says xyr trans identity is connected to xyr organizing work.

“I think the ultimate benefit I’ve seen from this work and from these ways of pushing is a more holistic understanding of oppression in general,” says Justice Gaines. “So, me as a black trans woman, I can’t separate those two things, which means I also can’t separate sexism from transphobia from racism, which means you can’t either.”

“This newfound ability to be like ‘we’re actually going to tow the line, we’re actually going to risk things, we’re actually going to pull down a statue, we’re actually going to climb a flagpole to take down a flag—those are things that I feel like have been activated because of queer people of color,” Justice says. “And, particularly, queer women of color, even, specifically, the Black Lives Matter movement founders.”

Justice also hopes that the ways gender is assigned and policed will change in the future: “If I ever have grandchildren, I don’t want there to ever be a point where the doctor decides what gender they are. And, even me, if I never do any medical transitions, I’m still a woman. I don’t want gender to have to be tied to the body you were born in unless you want it to be. For me, even transgender ultimately is a term that should be phased out.”

The experience of being out and queer, especially as a member of a queer community that is at risk of persecution, is to learn to rise up against such oppression.

“I think being gay—especially if you’re persecuted or you’re bullied and you decide to come forward and use your own experiences and trauma to change the world for other people—that has everything to do with the way that you are and the fact that you’re gay,” Lana says.

“Sooner or later Russia’s going to get there,” Lana says, describing a world in which gayness is so normal and accepted that people have no fear of losing their rights, a world in which a stranger wouldn’t automatically assume that every woman must be with a man. “The question is when and how many people will die in between … we’re not there yet.”

The impacts of queer identity are playing out in physical spaces—from human rights’ rallies to new stories for film scripts to the radical act of small-scale, local, holistic farming.

“It’s the only reasonable, sustainable future—if we all grow food everywhere,” Lindsey Medeiros says. “The more that we learn about where our food actually comes from, the more we learn about how unjust it all is, the whole system—from the way that the practices of industrial agriculture is stripping the soil and essentially uses slave labor and is poisoning watersheds, land, and air. Growing it where we live and eating that food is just an immediate connection to the earth—you’re grounded.”

Lindsey has noticed more queer people joining the farming community. It might not be a coincidence. “If you’re used to rebelling against gender stereotypes or gender norms or who you’re supposed to love or what you’re supposed to do with your body, you’re also open to the idea of rebelling against just the basic thing, food in your mouth, four times a day, and where that’s coming from and who makes it,” she says. “It is kind of

a rebellion.”

Of what consequence is the queer rebellion, of purple lipstick against a bearded face, of two women locked in an embrace, of naming ourselves and asking that others call us by our names—of being open to the idea that there is a brighter future ahead for the building? What we have is not enough. Every furrowed brow, every questioning look, every life-threatening act of being—that is in itself an act of facing down the old guard, of fearlessly bucking broken trends and creating the vessels in which our communities can live out loud.