UNKNOWN FIELDS DIVISION by Kate Davies and Liam Young

Barrow ocean edge. Photo by Dessi Lyutakova

Prologue

Far from the metropolis lie the dislocated hinterlands that support the mechanizations of modern living. The city is thoroughly embedded in a global network of landscapes and infrastructures that are too often forgotten, unseen, or ignored.

In Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad sets the narrator of the story, Marlow, on a boat on the Thames, the city glistening, serene behind him as he recalls a voyage into the unknown. In doing so, Conrad sets the familiar world of the city in direct contrast to the distant continent in which Marlow’s voyage into darkness unravels. The exact location of this voyage remains obscure in the text, uncertain next to the certainty of the departure point. The “biggest and the greatest town on earth,”2 the site from which he embarks—the known from which we relate to the unknown—might be read as the true ground for the narrative. It is both focal point and backdrop. “And this also,” says Marlow, “has been one of the dark places of the earth,”3 weaving the two together. When the familiar is implicated in the framing of the unfamiliar, Where do we come from? is as important as Where are we going? This is the dialogue at the center of the Unknown Fields Division’s work.

The Unknown Fields Division is a nomadic design studio that ventures out on biannual expeditions to the ends of the earth to explore extreme landscapes, alien terrains, and industrial ecologies. With groups of students and embedded collaborators, The Division reimagines complex realities of the present as sites of critical and speculative futures. The Division aims to remap the city and the technologies it contains, not as a discrete, independent collection of buildings and technologies, but as a networked object that conditions and is conditioned by a wide array of local and global landscapes. By developing an atlas of supply chains from consumption back to ground source, we can begin to understand the complex connections that exist between our everyday lives and a wider global context.

The emphasis of this research is to catalog sites along the global supply chain as a productive process. In order to speculate on how design may play a role in developing new cultural relationships with the inevitable by-products of industry—a changing climate and an anthropocentric world—we should first attempt to understand that world by bearing witness to some of these emerging infrastructural landscapes. These territories must be lived, experienced, and chronicled; but ultimately, they must also be reimagined. This complex web of interconnections and landscapes that gives shape to our world is too intricate to fully understand, but through storytelling and designed scenarios we can start to relate to that complexity in meaningful ways; and we can use these imaginative leaps to test our responses to possible futures. For The Division, the journey is the site, along which we construct a series of parallel narratives and partial fabrications and chronicle some probable fictions we have imagined in response to the improbable truths we have witnessed. As architects, we have the ability to construct realities for others to inhabit, to help shape cultural narratives and inform the way we collectively think about the world. When considering these landscapes, it is critical that we engage with the stories our culture constructs around them. Whether political spin, science fiction, nature documentary, environmental protest, disaster film, fairy tale, folklore, or scientific analysis, these narratives have merit. By understanding the mythology and stories of these distant landscapes, and disrupting or intervening within them as a second site, we can bridge the gap between the here and there.

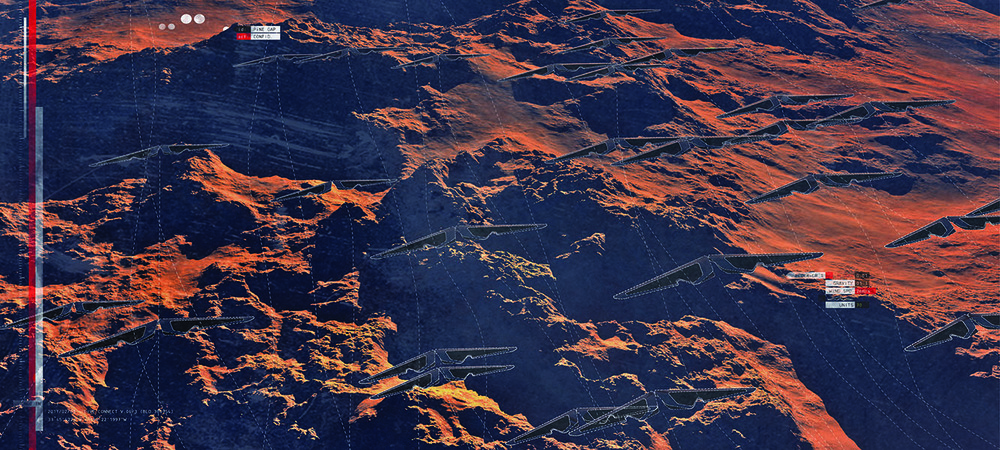

“Gravity One,” by Oliviu Lugojan Ghenciu. Australia Expedition

Traversing a Speculative Supply Chain

Here, we narrate a scenic journey with The Division along a speculative supply chain. It is a field guide through the science-fictional landscapes of the present: the landscapes of technology, and the technologies of landscape. It is a trajectory woven from some of the very real, physical sites The Division has explored across the last few years. Stitching these places together forms a new territory for us to inhabit, a city of logistics and trajectories, of shifting resources and distributed ground. It is a space that is at once nowhere and everywhere.

The Unknown Fields supply chain begins 1km below the surface crust of the Earth. The ground steams and rumbles as The Division stands in a new shaft of the Wiluna Gold mine, on the edge of the Western Desert in Outback Australia.

The Division will follow the material of this excavated landscape of caves and canyons as it is scattered across the earth. We each have a little piece of Wiluna on us now, in our pockets—0.034grams locked away in our mobile phones. We travel up through the gold fields and monster iron ore mines, following the two-kilometer long trains that drag the mountains out of the Outback and onto colossal ships bound for China to build cities for a rapidly urbanizing population. Here lies the shadow of those cities, the silent twin: the void where a landform once was. These are the dislocated resource sites that support the world we are more familiar with. Australia’s is a landscape whose material has been exploded into a global constellation: from iron ore destined for the popup cities in China to bauxite for aluminum smelting in Iceland; uranium for UK nuclear reactors to gold for plating connections in supercomputers modeling climate change in Alaska; food grade titanium to paint “m&m” on candies sold in a convenience store in Los Angeles to diamonds for sharpening knives in a sushi restaurant in Tokyo.

This vast infrastructural geology is cut out of the narrative landscape that embodies the creation stories of the Australian Aboriginals. Aboriginal dreamtime narratives speak of an era when the ground was soft and creation beings shaped mountains and rivers, when the rainbow serpent slinked across the ground to create a river, and a wild dog came to rest to form a mountain. These origin stories and ceremonies are now spun together with the ghosts of modern technologies. Explosives, diggers, and drills have replaced the slow erosion of rivers and winds. The Division follows a railway to Port Headland, where iron ore is stockpiled for export to China. Here we meet the aboriginal painter Lorraine Sampson, standing in the red dust blown from the carriages, “watching the trains take her country away.”

Mining survey planes track back and forth, laser-scanning the earth in search of the topographic anomalies that indicate pockets of undiscovered minerals in the ground. The scans locate a field to be core sampled, creating a geological map of the ore body below ground, a void in waiting. Traditional paintings of dreamtime stories have often been used to support land rights claims and are set in relation to the narrative of a fluctuating market that also lays claim to this landscape. The technologies with which this ground is surveyed and recorded also become the political means through which groups claim ownership over it.

The Division moves along the supply chain to visit the Wiluna mine design office in Perth; we watch the shape of the excavation change as the variable gold price is entered into the engineering software there. As the gold price rises, it becomes more economical to mine areas of lower gold ore concentration. The price drops, and the virtual mine shrinks as the software focuses the next cut around deposits of richer gold ore. Cut by cut, the fluctuations of the gold price are etched into the ground of Western Australia at the scale of the Grand Canyon. The steamy black void in which The Division previously stood is a live graph, a wormhole shaped by the frequency of electronic trades in London and New York. Gold is extracted from this ancient ground so it can be quantified and weighed. It is shipped across the world from one hole in the ground to another, to be stored below the surface once more in the vaults of HSBC and the Federal Reserve. Here, the majority of this material remains, to be traded virtually. The gold’s value is a fiction, embodied in a block of material wrung like blood from a stone, siphoned from vast tracts of land, only to sit, trapped, back in the earth.

This landscape of conflicting narratives and value systems raises difficult questions about our role as its custodians.

We continue along the mineral train line, rumbling toward the vast ports of the Western Australian coast. Everything in Port Headland is painted red, dusted in the rich ochre of the interior, blown from the tops of stockpiles and loaders that fill immense ships bound for distant lands. Tanker by tanker, an ancient landscape is being atomized and redistributed.

The bauxite mined in the Western Australian Outback is shipped as alumina to the edge of the Arctic, ready to harness Iceland’s outpouring of energy for aluminum smelting. We travel with it to this next stop on the supply chain. An excess of geothermal energy makes this island an oasis in a world shaped by power consumption. Energy here is harvested at 3 cents per Kwh—in the rest of the world, production ranges from 7 – 20 cents per kWh—and Iceland is rushing to create new industries to put it to use. This “clean” energy makes it economically viable to ship raw material extracted from half a world away here for processing, only for it to be sent back across the planet again for consumption. Alcoa runs an aluminium smelter near the town of Reyðarfjördur, which contains a hydroelectric power station with twice the energy output as all those used to power the rest of the country put together. Iceland’s unique resources flip the usual narrative about energy on its head.

“Here Be Dragons,” by Will Gowland. Alaska Expedition.

Iceland is 30 milliseconds from Alaska, via the FARICE-1 and ARCTIC FIBRE undersea data cables. The Division clicks “cheap flights Alaska,” two price-comparison windows open, and we contemplate our carbon footprint—but not for the reasons you might think. The servers that enact this single search consume approximately the same amount of energy it takes to boil water for one cup of coffee. Contemplate the number of searches queried in any given second around the world, and it comes as no surprise that the carbon footprint of the IT industry is set to overtake that of the airline industry by 2020. Internet giants and their server farm empires are the newest industries to capitalize on Iceland’s “guilt free” energy.

Here, digital technology is caught feeding. The Arctic North is becoming the home of the world’s data; the ephemera of the cloud—its invisible web of virtual connections—finds an extraordinary physical form in the volcanic deserts of Iceland. Standing beside the vast server racks, our faces are illuminated by thousands of blinking LEDs flashing with every email, search, naughty chat, and magnum opus. These machines need little besides cool temperatures and cheap power to keep running. This ethereal landscape, laced with folklore and boiling with an abundance of energy, is the incubator for the new stories we may tell ourselves.

The Arctic is more familiar as the protagonist in current environmental narratives than as the site where the complexities and contradictions of the energy debate are playing themselves out. The Division follows the data stream—the information supply chain—from one Arctic information hub to another, from geothermal warehouses to a large white room in Fairbanks, Alaska. At the Arctic Region Supercomputing Centre, we meet a supercomputer called Pacman, with banks of parallel processors performing trillions of operations per second, flanked by entire rooms full of data tapes. Each tape is full of readings and measurements, extrapolated figures and complex computational models. Mind-boggling numbers are involved as these computational behemoths carry out the task of predicting the future. This is a major hub in the global feedback system, where the effect of human activity on the planet’s ecology is assessed and extrapolated. We are reminded that now, as never before, our actions in a city halfway across the world have major implications on a faraway landscape we may never visit.

Jökulsárlón iceberg lagoon. Photo by Liam Young

Pacman computes climate and weather forecasts, modeling sea ice formation, arctic-ocean dynamics, ecological systems, and resource depletion. As our thirst for certainty about long- and short-term futures demands data at ever finer resolutions, places that support increased computing power relay information about complex natural processes and news of pressing environmental concerns to all corners of the world.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), a stretch of landscape in northern Alaska, is caught in the process of becoming part of an international supply chain. In a café in Anchorage, we meet an oil lobbyist for Arctic Power. He discusses a possible future of the ANWR, arguing that the US has no option but to drill there. To support his claim, he reels off an exhausting list of products made from oil: the plastic spoon in his hand, the fertilizer for the food we are eating, our medicines, cosmetics, and clothes, among others. The computed figures and predictions convince him that the ANWR will one day produce a million barrels of oil a day. Others interpret the same figures very differently. Earmarked as a future oil field, environmentalists call ANWR an irreplaceable haven for wildlife. It is a place monitored by environmentalists and speculators alike, and it is woven with conflicting narratives for its future.

Our supply chain comes to an end in a landscape in limbo at the top of the world. The Division lands on an icy runway at Barrow, on the far north coast of Alaska. It is winter solstice, and we slip into the darkness of an endless night. We stand on the frozen Arctic Ocean, its landward edge illuminated by streetlights along the shorefront. This is the landscape Pacman is thinking about. Here, climate scientists and Inuit work together to divine the future of this landscape. They watch this place. The Inuit compile ice diaries from careful observation and share ancestral knowledge. The scientists consult delicate instrumentation and differ in their outlook fundamentally. There is a thick streak of determined pragmatism from the Inuit community; as a culture, they approach change with confidence in their own ability to adapt, and so embrace multiple future scenarios with openness and resourcefulness. Environmental scientists, on the other hand, assemble their observations into climate forecasts with the hope of predicting the future as precisely as possible. The Far North is landscape as science experiment; it is a predictive model of itself, informing the future strategies of global environmental and energy policy penned back in the metropolises it supports. A distant landscape, conditioned by and conditioning the cities closer to home. A landscape mined for data as well as resources. A landscape measured in retreating ice and remaining barrels of oil. It is supply chain territory, precious and fragile, violent and terrifying.

Returning Home

As we come to the end of our travelogue, from the Antipodes to the North West Passage, we are reminded again that our point of view—the here from which we relate to there—is a large part of the story. Both of these terms presume a Northern European origin. Antipodal: the point diametrically opposite a given location on the globe, namely, Europe. North West: a location that assumes a South East from which to view it. We are aware that the connections between these places may tell a more accurate story than the nodes.

This has been a narrative voyage through just a few of the sites we have visited with The Division over the last 4 years. They are sites that offer us a new perspective from which to understand the emerging conditions we are designing for. These sites are landscapes where we find the future in the present tense, that act as condensers of wider issues we relate to only in an abstract sense from our more familiar cities. They are places on the margins of our knowledge, where issues such as climate change, resource depletion, declining biodiversity, and pervasive technologies play out with more immediacy and more urgency than anywhere else on the globe. They provide glimpses into alternative futures and form test beds for designers to critically evaluate the implications of emerging technologies.

Architects operate in the fertile ground between culture, nature, and technology. We are in a unique position to synthesize diverse and complex factors, to pose alternate scenarios and counter narratives, and to communicate them with imagination and precision. The Unknown Fields Division aims to prototype alternative ways of thinking about and acknowledging this complexity. If we can reveal this hidden cartography, we can begin to acknowledge the interconnected nature of place and explore new ways to navigate this complicated planet. We are a generation privileged to bear witness to this emerging world. This is a powerful place to be, on the very edge of the potential for change.

“Port Headland Iron Ore.” Photo by Oliviu Lugojan Ghenciu.

Kate Davies is founder of the multidisciplinary group LiquidFactory. Kate teaches diploma Architecture courses at the Bartlett School and the Architectural Association in London and regularly runs international design workshops.

Liam Young is an architect who operates in the spaces between design, fiction and futures. He is founder of the think tank Tomorrows Thoughts Today.