Arctic Commons

A collective future

by Gavin Zeitz

A COLLECTIVE FUTURE

The Arctic Commons envisions a world where geopolitical cooperation and transnational partnership generate an attitude of planetary collectivism that promotes future stability in the Arctic and the rest of the world. The declaration for an Arctic Commons lays out a new constitutional framework focused on prioritizing

the rights of marginalized indigenous communities, at-risk wildlife species, and critical environmental habitat zones. As a document, the declaration represents a new ideological paradigm for the 21st century that abandons the all-encompassing neoliberal agenda and paves the way for the restoration and reclamation of disenfranchised cultures, traditions, and ecosystems.

To move on from a capitalist, growth-driven mindset of dictating territory, we must dissect the current situation. We must ask ourselves—how can these future policies exemplify a reconciliatory form of kinship between economic activity, the environment, and human inhabitants?

This project questions our understanding of the Arctic at a range of scales and investigates how landscape architects can re-politicize their design intentions by applying design research, visual representation, and narrative to encourage action around critical landscape issues. Through the use of a diverse set of narrative and visual tools, complex issues can be distilled to effectively stimulate public interest and engagement. The

Arctic Commons looks onward to a future where geopolitical forces are shaped by ecological processes and cultural history. In effect, the declaration lays out a path forward to a new Arctic status quo.

THE THREE GREAT SHIFTS

There have been three critical paradigm shifts in the spatial organization of the Arctic: 1. the land bridge migration and settlement around 16,500 years ago, 2. early Euro-American colonization roughly 300 years ago, 3. militarization and neoliberal expansion. A looming fourth wave of spatial reorganization imperils the future of the Arctic and threatens the common heritage of humankind.

Early attitudes depicted the Arctic as a terra nullius, a no-man’s land and vacant territory of sublime natural forces. We now know that this assumption was ignorant and inaccurate, but the consequences and conditions which grew from this attitude still plague the communities, cultural heritage, and ecology of the North. Going forward, it is critical that we realign our understanding of the North as a land for all, or a terra omnis. The North and South poles of the world are critical environmental balancers keeping the climate at a homeostasis. Large climatic shifts in these regions will alter global weather and climate to an unknowable, albeit disastrous, degree. We must respect the Arctic as a geography of rich, unique cultures and ecosystems, while acknowledging the reality of international geopolitical pressure to utilize the Arctic for fuel-saving shipping routes and natural resources.

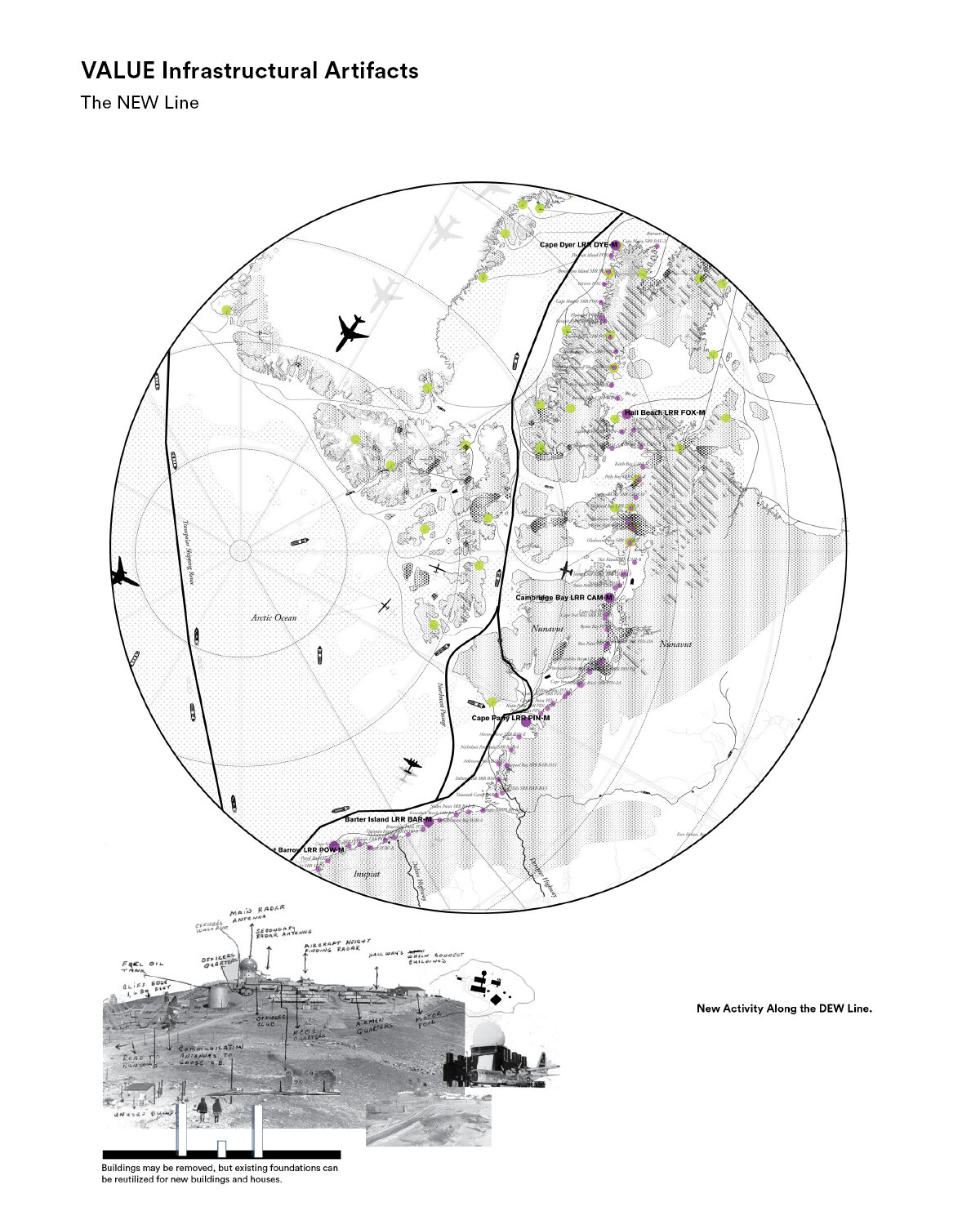

The remote nature of the Arctic communities has often led to tragic government policies which have eroded the cultural heritage of the first settlers of the North for centuries. The Cold War brought military occupation, government control of native lifeways, forced relocation, and environmental degradation and contamination. We’re currently at the brink of environmental collapse in the region and we can easily foresee a future with an ice-free Arctic. Our future policies in the Arctic will make or break the ecosystems and cultures tied to environmental stability. In order to address these issues, we need to subvert the classic, persisting notion that the Arctic is a terra nullius and envision the region as a terra omnis.

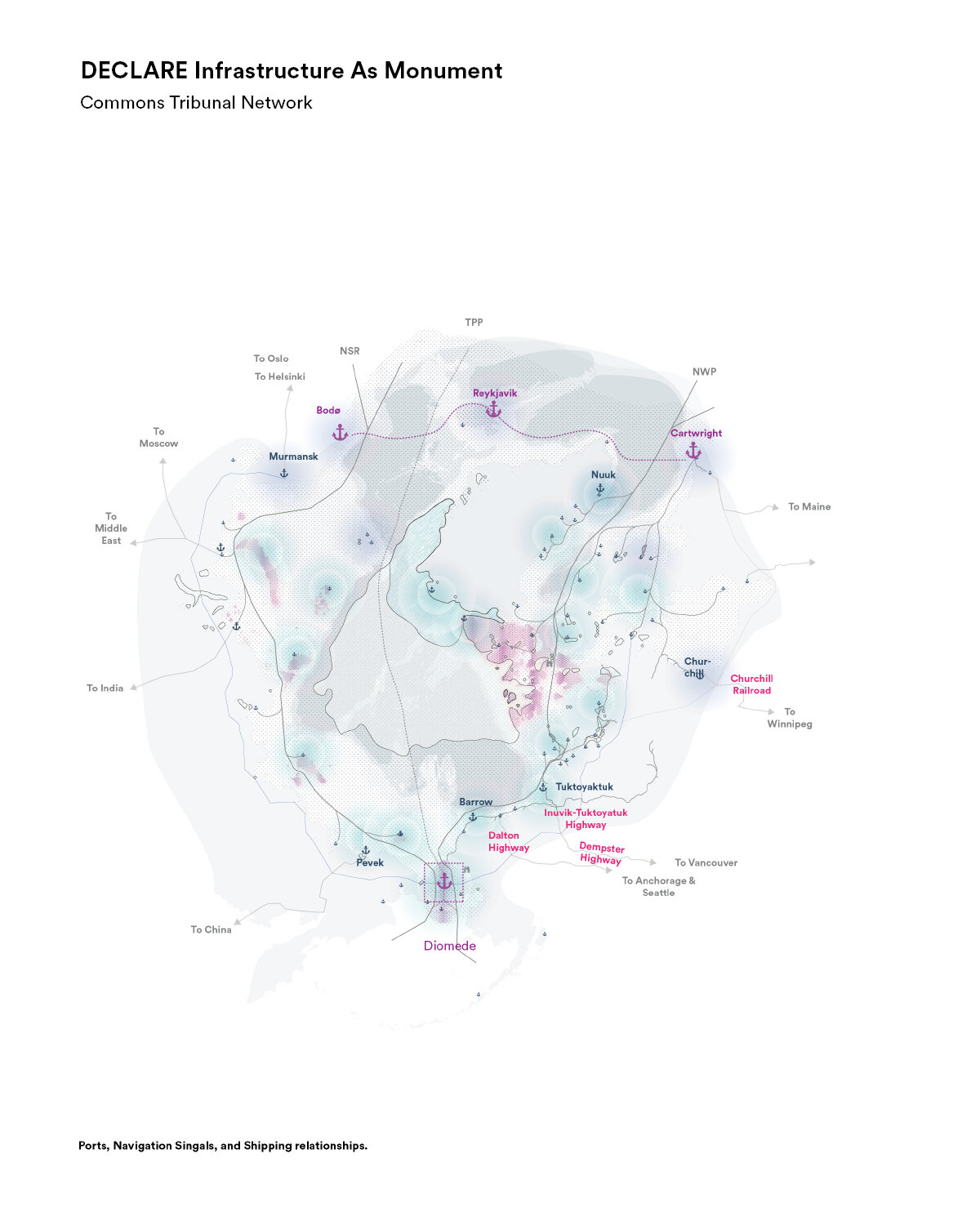

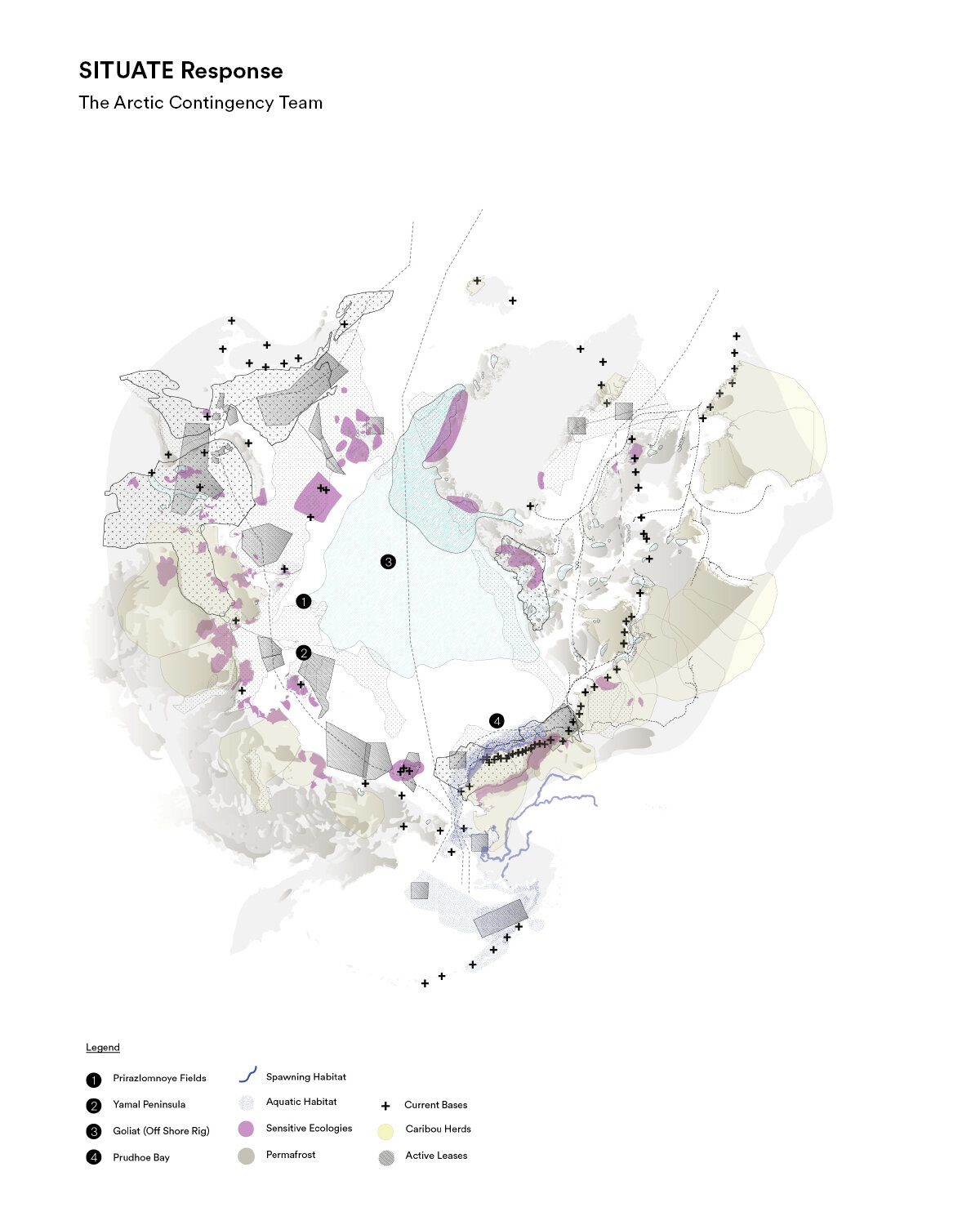

MAPPING FLUID TERRITORIES

The Arctic is in a constant state of flux, a perpetual contradiction between fluid, solid, and somewhere in between. The edge between land and sea changes from day to day, year to year, century to century. This provokes a host of challenging questions—how do we define the boundaries of a shifting territory? How do we create flexible networks that can monitor and adapt to fluctuations? Currently the region is defined by arbitrary and antiquated cartographic standards; anything above latitude line 66.66 is considered the Arctic.

However, there are a multitude of other lenses through which to define this malleable territory—exclusive economic zones, caribou habitat zones, oil field leases, land conservation tracts, ground conditions, indigenous languages, or transportation networks. This set of maps represents the esoteric and contradictory definitions we have adopted as geographic delineations of territory while also shedding light on the complexity of the problem. There is no one easy fix, but superimposing the data exposes opportunities and potential conflict areas that allow for a prioritization of interests. In certain areas, habitat may be given precedence while, in others, it may end up being an infrastructural opportunity that takes priority. The composite maps lead to a series of strategic cartographic approaches to situate emergency and environmental response stations, provide public access, value existing cultural artifacts, and harness the power of climate change.

From left to right: On-Structure Community, Metal Mesh Path from Dock to Shelter, Arctic Commons Gateway

MATERIALIZING THE ARCTIC COMMONS

To understand the ways an Arctic Commons would manifest spatially, we have prototyped six landscape interventions. These six landscape propositions each zoom into a specific site and shrink the regional strategies down to the scale of human experience and constructibility. Each of the six prototypes engages an emergent issue in the region as well as a different stakeholder.

1. Public-use facilities provide adventurers, researchers, emergency response teams, and hunters with shelter in remote regions. The stations make use of legacy infrastructure and vernacular materials such as out-of-use radar stations or shipping containers.

2. Renovated military bases often found on high and stable ground are repurposed as new communities for climate refugees who wish to remain in the area.

3. New shoreline constructions—shelter platforms—emerge at the eroding coastal edge of a permafrost-dune and provide stable ground along the disappearing coast. As permafrost melts away, the platforms eventually become a part of the sea while maintaining the communities’ deep ties to place.

4. Similarly, as the ice disappears, hunting platforms are built into the coastal waters to enable fishermen to continue their cultural traditions of hunting sea life for sustenance.

5. At the Bering Strait, a sublime building links the North American and Asian continents with the construction of the Arctic Commons Tribunal, a center for global diplomacy and sustainable shipping logistics. A tollway at the strait taxes passing ships; the funds it generates contribute to the Arctic Reconciliation Fund, supporting local initiatives in education, health, community engagement, and renewable industry.

6. In Greenland, a new model for sustainable resource extraction emerges: the Arctic Sand Commons. This initiative capitalizes on the catastrophe of glacial melting to empower local communities to harvest and export the massive quantities of sand, gravel, and silt fertilizer deposited by glaciers during their retreat. The material is dredged from fjords and shipped to coastal areas threatened by sea level rise for use in restoration projects. The material goes to marsh, dune, and beach reconstruction; as well as aggregate for constructed storm barriers. Locally, the Arctic Sand Commons helps Greenland become a monetarily independent territory that is able to retain its younger workforce and continue its cultural heritage of working the land.

ONWARD, NOW

The Arctic Commons is not a speculative approach to the issues facing the global North but, rather, a critical response to the lack of urgency in addressing these issues to date. Our current political systems will not get us out of this mess; we need to overhaul the standard protocol and reinvent our entire approach, mapping and constructing landscapes that are by and for all. This can only be done if marginalized social and ecological communities are given power. We must reconcile our political differences and invent new forms of geopolitical governance that are collaborative and multi-scalar in their approach. The time is now to think of our northern landscapes as vital to the future of humankind. The Arctic must become a terra omnis.

Gavin Zeitz is a landscape architect whose work investigates the relationship between territory, ecological systems, and cultural landscapes. His work focuses on complex landscape issues and how they are catalogued, organized, and represented to a variety of disciplines and stakeholders. His work includes research projects investigating the future of Arctic landscapes, cultural landscapes of climate change, dammed rivers and watersheds in New England, and urban infrastructural space. In his research, Gavin has

spent time traveling throughout the global North, specifically in Alaska, Greenland, and Iceland. Gavin is currently a critic at the Rhode Island School of Design, as well as a designer at LANDING Studio in Somerville, MA. In the past, he has worked for the Dredge Research Collaborative as well as the UVM Spatial Analysis Lab.